How will Brexit affect UK agricultural land values (and why does it matter)?

Posted by Deb Roberts on Thursday 8 February 2018

The value of agricultural land is critical not just for those intending to buy or sell farmland but to all those involved in the agricultural sector and others holding land as an investment asset. It is therefore surprising that, in and amongst all the other discussions on the future of British agricultural policy, very little has been said on how Brexit will impact UK farmland values. This blog reviews the factors that determine agricultural land values. I argue that an important (but unintended) impact of historic farm support policies is that they distort farmland prices. As such, any change in the nature of UK agricultural policy will impact land prices, resulting in both gainers and losers in the sector.

Image: Author

Unlike most other goods or inputs, farmland performs many functions each of which contributes to its overall value. It is a necessary input in the agricultural production process - all farmers need at least some land to produce farm commodities – and, at the same time, land is a capital asset and source of wealth. In part due to tax advantages, in part because its returns are independent from those of other investment assets, farmland has been attractive for investors looking for a diversified portfolio.

In addition, land provides benefits in terms of privacy, recreational opportunities (walking, hunting, fishing), biodiversity and several other ecosystem services. Some of these benefits are retained exclusively by land owners but others are shared with wider society.

While allowances are made for the non-agricultural functions of land, traditional explanations of the price of farmland concentrate on its role as an input in production. In theory, the price of a parcel of land should be related to the value of future rental income streams from farming that land. Hence the widespread use by rural surveyors of maps classifying land according to productive capability (for example see here). In this way there should be a link not just between land quality and land prices but also between vacant possession and tenanted land prices.

Before the Second World War this approach to understanding land values worked well. For example, Brian Hill and Ken Ingersent (in their 1982 book) reported an average vacant possession price between 1936 and 1939 of £62 per hectare, with the average price of tenanted land during the same period just slightly lower at £57 per hectare. Gross rents at the time were £2.97 per hectare, which, assuming a 5% discount rate, pretty much explains exactly the price levels. However, since the early 1950s, farmland prices have been far higher than the present value of discounted rents would suggest, by the early 1970s as much as 10 times higher, even after having allowed for inflation. Further, a large gap between vacant possession and tenanted land emerged. The high price of farmland has had major implications for structural change in the UK farm sector and has contributed to an increase in owner-occupation.

So why has this happened? Economists would argue that a key driver of high land prices has been farm support policies and that the problem is caused by land being a “fixed factor of production”.

To explain, the 1947 Agricultural Act included a clear commitment from the UK government to protect farm incomes and encourage growth in farm output. When the UK joined the European Community in 1973, the likelihood of continued high levels of support for the sector became even greater. At that time, the main form of support used in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was intervention buying which kept farm output prices higher than would otherwise be the case. Farmers strove to maximise incomes by adopting a high-input high-output approach to production and this increased demand for all agricultural inputs including machinery and other produced inputs (agrichemicals, agricultural services). New firms were attracted into these input industries, with competition ensuring that any surplus profits from the extra demand soon disappeared. However, although there was an increase in the intensity of land use and more land was converted to agricultural production, the supply of farm land is ultimately fixed. As a result, the increase in demand for land led to an increase in agricultural land prices, and this was exacerbated by the increased attractiveness of land to investors from outside the sector. To give an indication of the magnitude of effect, Bruce Traill published a scientific paper in 1979 estimating that every £1 increase in CAP intervention support prices in the 1980s led to a £10 increase in the value of land.

Although the form of support provided to farmers in the EU has changed dramatically over the last few decades and is now less market distorting; support payments are still tied to land and this sustains land prices beyond those that would otherwise exist. Many other economic studies, in different countries under different agricultural policies, have confirmed that the value of land comes primarily from two main sources – farm production and government subsidies – and that, because government payments are more stable, they are discounted less than market-based returns. This results in them having a disproportionately positive impact on the value of land.

So, given that farm support has historically been a major influence on UK land prices, how will Brexit impact the value of farmland? Evidence of any impact to date is limited by the thin nature of the land market (less than 1% of total farmland tends to be traded in any year) and also the highly variable quality of farmland. In the short run, the drop in the value of sterling since June 2016, widely attributed to Brexit uncertainty, has helped sustain overseas investment interest in UK farmland. However, unless there is further sterling devaluation, this is unlikely to continue with decisions of both overseas and British investors being based on relative returns from agricultural land ownership compared to those available from other assets. Much will depend on whether or not the tax benefits associated with farm land ownership are retained. If they are, any significant price fall may be avoided.

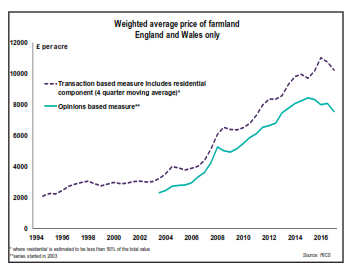

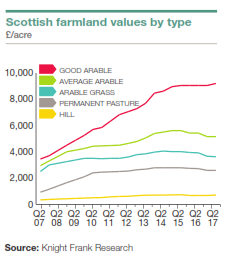

Figures 1 and 2 suggests that having reached a peak in 2015, farm land values in England and Wales have dropped by about 9% over the last year, while Scottish land values rose very slightly in the first half of 2017 (0.6%) after a fall in 2016 but with large differences emerging between land types. Most surveyors are predicting a further decline over the next 12 months (https://www.rics.org/Global/RICS_RAU_Rural_Land_Market_Survey_H1_2017_Summary.pdf).

Figure1: Farmland prices, England and Wales (RICS, 2017) https://www.rics.org/uk/knowledge/market-analysis/ricsrau-rural-land-market-survey-h2-2013/

Figure 2: Trends in Scottish farmland values by type. http://content.knightfrank.com/research/443/documents/en/scottish-farmland-index-h1-2017-4814.pdf

The extent of any land price reduction associated with Brexit will depend on the form of support that is provided and the future competitiveness of British farmers. While any type of support tied to land will impact land values, the proposed duration of support and the limitations placed on production activities over that period will be key factors as will the nature of the agricultural trade agreements that are reached via the Brexit negotiations.

If farm land prices do decline, there will – as always - be gainers as well as losers. Arguably maintaining a situation where farmers are “asset rich but income poor” isn’t good for the long run viability of the sector so a situation where land values return to a level which allows competitive farmers to expand would be good. Further, a fall in land values would lower the barriers that face new entrants to the sector and it may lead to a readjustment in the balance of tenanted and owner occupied land, and greater diversity of ownership.

Of course, it is possible that the biggest threat to farm land values is not Brexit but new technology. The advent of vertical farming potentially removes or at least challenges the assumption that land is fixed in supply and will alter the relative importance of factors such as land quality and location. The only certain conclusion is that there are interesting times ahead for land surveyors.

References:

BRUCE TRAILL; An empirical model of the U.K. land market and the impact of price policy on land values and rents, European Review of Agricultural Economics, Volume 6, Issue 2, 1 January 1979, Pages 209–232, https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/6.2.209

Hill, B. E. and K. A. Ingersent (1982). An Economic Analysis of Agriculture, Heinemann Educational Books.

Comments

Post new comment