The digital footprint of #StormArwen and the disruption of water supplies

Posted on behalf of Diana Valero, Rowan Ellis, Rebecca Gray

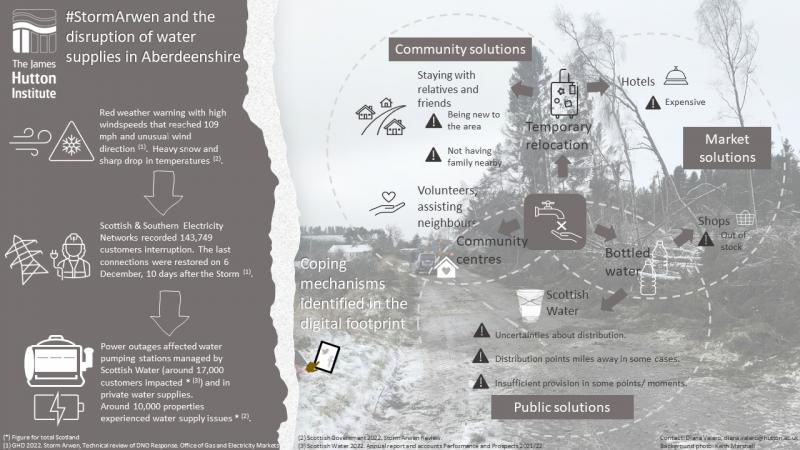

A year ago, Storm Arwen battered Scotland with gales of almost 100km. The northeast region was particularly badly hit. Thousands of households in Aberdeenshire lost their power and water supplies and, for some, this situation lasted for days.

The footprint that Storm Arwen left on our landscapes was impactful – and still visible today. Millions of trees were blown down and woodlands and forests completely transformed. Storm Arwen also left a digital footprint as people and communities, utility companies and public agencies used social media to communicate risks, ongoing issues and information about available resources.

Reconstructing the crisis through social media

During the last few months, the Macaulay Development Trust Fellowship in Rural Water Security has been looking at this digital footprint to reconstruct how the crisis developed, the impacts on water supplies and the solutions and coping mechanisms that people and communities put in place.

Looking at the digital footprint allows us to reconstruct what happened during a period of crisis, without asking people to recount potentially distressing or difficult memories.

To carry out this work, we analysed the posts and comments on two of the most popular digital social media platforms, Facebook and Twitter, using specific strategies of data collection tailored to their audiences, privacy and data policies.

On Twitter, for example, data from almost 60,000 tweets was collected through the Twitter dedicated API for academic researchers. On Facebook, where collecting data for research purposes is more complex and nuanced, data was collected anonymously (without personal identifiers) and only from selected organisations that used their Facebook page as a means of public communication and the public comments posted in those posts (more than 2,000 posts and comments reviewed).

Power out and water disrupted

Lack of access to water was the tip of the iceberg in a situation that was underpinned by large scale disruptions to the power network. Without electricity, water could not be pumped, causing interruptions in the public supplies (provided by Scottish Water) and more widely to private supplies.

Lack of electricity also, in many cases, compromised the ability to heat homes and to cook and made it impossible to power appliances, including medical equipment. It also compromised communications, with digital internet and phone services down in many areas, not to mention the challenges of keeping communication devices charged.

Connections by road were disrupted. Fallen trees blocked roads and paths. The storm also brought very wintery conditions, with cold temperatures and snowfall. Even in cases where water supplies were not impacted, people worried that, without heating, water pipes could freeze and burst.

Even after power was restored, many experienced ongoing uncertainty as some communities and households suffered intermittent faults in the weeks that followed.

Community support

Community centres were opened across Aberdeenshire to provide food, water and access to charging points and in some cases showers. The community spirit and solutions offered by communities were key in the response to the crisis and the digital footprint reflects that.

Posts from Aberdeenshire Council, for instance, recognise the role and richness of the community action (“There is a wealth of local community activity and support taking place across Aberdeenshire…”). People offered help and assistance to family members, friends, neighbours, volunteers and workers responding to the crisis.

People offered to communicate with the utility providers, offering shelter and hots drinks and dropping off bottled water. There was evidence of particular concern and care for elderly and vulnerable people with water provision.

Community networks and support systems played such an important role that people who had just moved into an area struggled to get help or navigate the resources available. There was also an expressed sympathy for people who did not have family around that could host them.

Remote living challenges

One of the coping strategies suggested by the utility providers was to check in into a hotel until the supply was restored. This solution was pointed out as an unaffordable solution for some (even despite that the expenses were supposed to be refunded later on by the energy provider). Moreover, in the rural context, where most private water supplies are found, households taking care of animals did not see relocation - albeit temporary – as an option. There was a feeling of being forgotten because by those living remotely.

While the Scottish Water-managed supplies were reconnected or an alternative solution provided (e.g. refilled by tanks) fairly quickly, the situation was different for people with private water supplies. In some cases, people with private water supplies were without safe and/or plentiful water for more than a week. During this time, those with private water supplies were advised to use bottled water or boil water before use.

Access to water

In many cases, getting bottled water was not straight-forward. The expectations about the delivery of bottled water were not always being matched. Some people asked why Scottish Water was not delivering bottled water. Others asked when and where it would be delivered.

Scottish Water committed to providing 10 litres per person, per day to affected households, but it was not specified if this referred to Scottish Water customers or if people on private water supplies were included. Some people likened the situation to when private water supplies had run dry during the summer and “the council” had helped them and wondered if there was a similar support in this case.

Even where there was delivery of bottled water, it was still insufficient in some cases. There were people that arrived at the distribution points (sometimes 20 miles away to their homes) to find that there were none left. The availability of bottled water was also very scarce in local stores and supermarkets. People who had to drive for miles to get supplies in the nearest welfare point wondered what people without transport options could do. Also, in some situations people were unable to leave their homes to source bottled water (at the time of Storm Arwen, there were still many isolating with or from Covid, for instance).

What the digital footprint tells us

This digital footprint highlights two types of responses to water insecurity: getting alternative sources of water and temporary relocation. The access to bottled water - a plastic intense and costly resource - was mediated by the proximity/remoteness to distribution points and surrounded by a large degree of uncertainty. Temporary relocation was not an option for everyone, depending on the existence of animals, personal connections, and available economic resources.

Of course, the picture that social media provides is partial. Out of focus are the experiences of many people: those who do not use social media (such as the elderly, those without regular access to digital communication tools);those who did not have access to social media in the time period given the power and communication networks cuts; and people who may have used social media (to connect privately or get informed), but did not participate in the more public conversations or who have added layers of digital privacy.

Still, the digital footprint of #StormArwen provides a large sample that gives us a useful starting point for studying the impacts of the crisis.

Next steps – filling in the gaps

In the next couple of months, we will be interviewing stakeholders and people who were affected by water provision cuts due to Storm Arwen. This will help us to investigate the medium and longer-term adaptive changes and transformations that may improve the resilience of the water supplies.

The focus of the interviews will be on any type of changes and new actions (resources, technology, institutional arrangements, social practices, individual and collective behaviours) that might have been adopted or considered during the last year that could have an impact on how people and communities can be better prepared for water supply disruptions in the future.

Comments

Post new comment