Using a different lens: Children as researchers

Posted by Katrin Prager on Wednesday 26 August 2015

Although there is plenty of research ‘on’ children and ‘with’ children, there is not much published on research that was done ‘by’ children, and no literature that covers research by children on greenspace. I assume this is due to the little education children receive about how to carry out such research, and if they do, the results are typically not publishable in academic journals. There is only limited guidance on how research skills can be taught to children and at what age, and how researchers can be encouraged to interact with children and engage with teachers. Why do I think this matters?

I think would it be useful if children were able to undertake research themselves, as it is a way of broadening their understanding of the world around them and their place in it. It can empower them, helping them to take ownership, and ultimately grow into responsible and reflective citizens.

So how might a researcher go about teaching research skills to children? A useful example comes from a social researcher called Mary Kellet, who designed a programme that allows children to learn about social research tools over the course of some ten weeks (see this research paper for a report of children’s research results). Taking her approach as a guide, I tried this myself. I followed a trial and error approach that was very much determined by the primary school I worked with and the classroom context. My aim was to teach the students (between 10 and 11 years old) enough about a social research method to allow them to investigate their use of greenspace – but I only had about 3 hours!

The children selected the topic they wanted to explore and developed questions for a questionnaire to be completed by their peers. They found out what children in the primary school used greenspace for, how far they would walk/ cycle to get there, and that their peers felt there was not enough greenspace in the town. All details can be found in the full paper and these reports. The paper also includes some tips on what to be aware of when working with primary schools, so that fellow researchers can benefit from my experience of engaging with students and teachers.

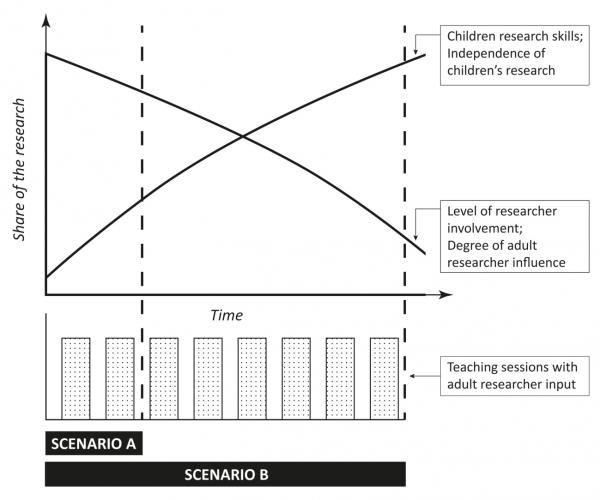

My observation, which echoes Kellett’s experiences, was that the more time allowed, the better the learning experience for the students and their research results. Children’s research skills and thus the level of independence with which they can carry out their research will increase if enough time can be made available to teach them the necessary skills. This cannot be achieved fully in a couple of sessions. However, in real life, the time that teachers, students and researchers can invest is generally limited. My idea is visualised in the figure, where the regular input from the researcher via teaching sessions is shown on the lower timeline. The share that the adult researcher has in the research undertaken is higher in the beginning and reduces over time as children gain skills. ‘Scenario A’ shows my example where input stopped after two sessions. In that case children gained less skills, with their research less independent and more influenced by myself, the adult researcher.

In ‘Scenario B’ the teaching session continues for a period of several weeks. The more time is invested into teaching research skills, the more independent the children’s research becomes because their research skills develop further. Results from the latter type of research are more genuinely a product of the children.

So, with enough time, children are able to undertake interesting research with results that are worth sharing. Furthermore this process of researchers interacting with children can be mutually rewarding, so it seems worthwhile to encourage more of this. However, academic journals are not commonly prepared to publish the outputs of research undertaken by children or adult non-academics, and some might say rightfully so. How then could we best share insights of children and other ‘unconventional researchers’? Such insights often don’t lend themselves to being forced into the format required by an academic journal. Might high quality blogs be established as an appropriate and accessible outlet?

Comments

Comment entitled: Excellent idea, submitted by Joanna Storie at 06:00, 28/08/2015

I spent many years at home with my children, part of that time home-schooling and doing freelance children's work for churches and conferences but I have now returned to academia and the thought of being able to bring these two aspects together sounds exciting.

You make a very valid point about the need for building research skills, much more so as school science lessons have become quite boring due to safety concerns. Here in Latvia an investigative mind is not encouraged due to its Soviet legacy and so building research skills at an early age is something I would love to explore as one means for revitalising the skill set of this nation. It will have a great benefit to the rural areas as investigative mindsets will enable rural dwellers to think creatively about their environment and how best to utilise it.

Post new comment